| Cover Page |

|||||

Produced by the CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group Version 7.1.1 April 2021 Editors: Chryssoula Bekiari, George Bruseker, Martin Doerr, Christian-Emil Ore, Stephen Stead, Athanasios Velios CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.26225/FDZH-X261 This page is left blank on purpose |

|||||

| Table of Contents |

||

| Automatically generated content | ||

| Introduction >> Scope of the CIDOC CRM |

||||||

The overall scope of the CIDOC CRM can be summarised in simple terms as the curated, factual knowledge about the past at a human scale. However, a more detailed and useful definition can be articulated by defining both the Intended Scope, a broad and maximally-inclusive definition of general application principles, and the Practical Scope, which is expressed by the overall scope of a growing reference set of specific, identifiable documentation standards and practices that the CIDOC CRM aims to semantically describe, restricted, always, in its details to the limitations of the Intended Scope. The reasons for this distinctions between Intended and Practical Scope are twofold. Firstly, the CIDOC CRM is developed in a “bottom-up” manner, starting from well-understood, actually and widely used concepts of domain experts, which are disambiguated and gradually generalized as more forms of encoding are encountered. This aims to avoid the misadaptations and vagueness that can sometimes be found in introspection-driven attempts to find overarching concepts for such a wide scope, and provides stability to the generalizations found. Secondly, it is a means to identify and keep a focus on the concepts most needed by the communities working in the scope of the CIDOC CRM and to maintain a well-defined agenda for its evolution. The Intended Scope of the CIDOC CRM may, therefore, be defined as all information required for the exchange and integration of heterogeneous scientific and scholarly documentation about the past at a human scale and the available documented and empirical evidence for this. This definition requires further elaboration:

The Practical Scope[2] of the CIDOC CRM is expressed in terms of the set of reference standards and de facto standards for documenting factual knowledge that have been used to guide and validate the CIDOC CRM’s development and its further evolution. The CRM covers the same domain of discourse as the union of these reference standards; this means that for data correctly encoded according to these documentation formats there can be a CIDOC CRM-compatible expression that conveys the same meaning. As part of the on-going work of keep the standard up-to-date, discussions on the types of bias present in the CIDOC CRM are in progress within the CIDOC CRM community. |

||||||

| References: | ||||||

|

||||||

| Introduction >> Terminology |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The following definitions of key terminology used in this document are provided both as an aid to readers unfamiliar with object-oriented modelling terminology, and to specify the precise usage of terms that are sometimes applied inconsistently across the object-oriented modelling community for the purpose of this document. Where applicable, the editors have tried to consistently use terminology that is compatible with that of the Resource Description Framework (RDF),[3] a recommendation of the World Wide Web Consortium. The editors have tried to find a language, which is comprehensible to the non-computer expert and precise enough for the computer expert so that both understand the intended meaning.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| References: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Applied Form >> Property Quantifiers |

||||||||||||||||||||||

Quantifiers for properties are provided for the purpose of semantic clarification only, and should not be treated as implementation recommendations. The CIDOC CRM has been designed to accommodate alternative opinions and incomplete information, and therefore all properties should be implemented as optional and repeatable for their domain and range (“many to many (0,n:0,n)”). Therefore, the term “cardinality constraints” is avoided here, as it typically pertains to implementations. The following table lists all possible property quantifiers occurring in this document by their notation, together with an explanation in plain words. In order to provide optimal clarity, two widely accepted notations are used redundantly in this document, a verbal and a numeric one. The verbal notation uses phrases such as “one to many”, and the numeric one, expressions such as “(0,n:0,1)”. While the terms “one”, “many” and “necessary” are quite intuitive, the term “dependent” denotes a situation where a range instance cannot exist without an instance of the respective property. In other words, the property is “necessary” for its range. (Meghini, C. & Doerr, M., 2018)

The CIDOC CRM defines some dependencies between properties and the classes that are their domains or ranges. These can be one or both of the following:

The possible kinds of dependencies are defined in the table above. Note that if a dependent property is not specified for an instance of the respective domain or range, it means that the property exists, but the value on one side of the property is unknown. In the case of optional properties, the methodology proposed by the CIDOC CRM does not distinguish between a value being unknown or the property not being applicable at all. For example, one may know that an object has an owner, but the owner is unknown. In a CIDOC CRM instance this case cannot be distinguished from the fact that the object has no owner at all. Of course, such details can always be specified by a textual note. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| Modelling principles |

||

The following modelling principles have guided and informed the development of the CIDOC CRM. |

||

| Modelling principles >> Reality, Knowledge Bases and CIDOC CRM |

||||||||

The CIDOC CRM is a formal ontology in the sense introduced by (Guarino, 1998).[4] The present document is intended to embrace an audience not specialized in computer science and logic; therefore, it focuses on the informal semantics and on the pragmatics of the CIDOC CRM concepts, offering a detailed discussion of the main traits of the conceptualization underlying the CIDOC CRM through basic usage patterns.[5] The CIDOC CRM aims to assist sharing, connecting and integrating information from research about the past. In order to understand the function of a formal ontology of this kind, one needs to make the following distinctions:

A formal ontology, such as the CIDOC CRM, constitutes a controlled language for talking about particulars. I.e., it provides classes and properties for categorizing particulars as so-called “instances” in a way that their individuation, unity and relevant properties are as unambiguous as possible. For instance, Tut-Ankh Amun as instance of E21 Person is the real pharaoh from his birth to death, and not extending to his mummy, as follows from the specification of the class E21 Person and its properties in the CIDOC CRM. For clarification, the CIDOC CRM does not take a position against or in favour of the existence of spiritual substance nor of substance not accessible by either senses or instruments, nor does it suggest a materialistic philosophy. However, for practical reasons, it relies on the priority of integrating information based on material evidence available for whatever human experience. The CIDOC CRM only commits to a unique material reality independent from the observer. When we provide descriptions of particulars, we need to refer to them by unique names, titles or constructed identifiers, all of which are instances of E41 Appellation in the CIDOC CRM, in order the reference to be independent of the context. (In contrast, reference to particulars by pronouns or enumerations of characteristic properties, such as name and birth date, are context dependent). The appellation, and the relation between the appellation and the referred item or relationship, must not be confused with the referred item and its identity. For example, Tut-Ankh Amun the name (instance of E41 Appellation) is different from Tut-Ankh Amun the person (instance of E21 Person) and also different from the relationship between name and person (P1 is identified by). Instances of CIDOC CRM classes are the real particulars, not their names, but in descriptions, names must be used as surrogates for the real things meant. Particulars are approximate individuations, like sections, of parts of reality. In other words, the uniqueness of reality does not depend on where one draws the line between the mountain and the valley. A CIDOC CRM-compatible knowledge base (KB) (Meghini & Doerr 2018) is an instance of E73 Information Object in the CIDOC CRM. It contains (data structures that encode) formal statements representing propositions believed to be true in a reality by an observer. These statements use appellations (e.g., http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n79066005[6]) of ontological particulars and of CRM concepts (e.g., P100i died in). Thereby users, in their capacity of having real-world knowledge and cognition, may be able to relate these statements to the propositions they are meant to characterize, and be able to reason and research about their validity. In other words, the formal instances in a knowledge base are the identifiers, not the real things or phenomena. A special case is digital content: a KB in a computer system may contain statements about instances of E90 Symbolic Object and the real thing may be text residing within the same KB. The instance of E90 Symbolic Object and its textual representation are separate entities and they can be connected with the property P190 has symbolic content. Therefore, a knowledge base does not contain knowledge, but statements that represent knowledge, as long as there exist people that can resolve the identifiers used to their referents. (Appellations described in a knowledge base, and not used as primary substitutes of other items, are of course explicitly declared as instances of E41 Appellation in the knowledge base.) |

||||||||

| References: | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Modelling principles >> Authorship of Knowledge Base Contents |

||||

This section describes a recommended good practice how to relate authority to knowledge base contents. Statements in a KB must have been inserted by some human agent, either directly or indirectly. However, these statements often make no reference to that agent, lacking attribution of authority. An example of such statements in the CIDOC CRM is information expressed through shortcuts such as P2 has type. In the domain of cultural heritage, it is common practice that the responsibility for maintaining knowledge in the KB is elaborated in institutional policy or protocol documents. Thus, it is reasonable to hold that statements which lack explicit authority attribution can be read as the official view of the administrating institution of that system, i.e., the maintainers of the KB. This does not imply that the knowledge described in the KB is complete. So long as the information is under active management, it remains continuously open to revision and improvement as further research reveals further understandings.[7] A KB does not represent a slice of reality, but the justified beliefs of its maintainers about that reality. For simplicity, we speak about a KB as representing some reality. Statements in a KB may also carry explicit references to agents that produced them, i.e., further statements of responsibility. In CIDOC CRM such statements of responsibility are expressed though knowledge creation events such as E13 Attribute Assignment and its relevant subclasses. Any knowledge that is about an explicit knowledge creation event, where the creator’s identity has been given, is implicitly attributed to be correctly referred to in the KB by the maintaining authority, whereas the responsibility for the content created by that event is assigned to the agent identified as causal to that event. In the special case of an institution taking over stewardship of a database transferred into their custody, two relations of responsibility for the knowledge therein can be envisioned. If the institution accepts the dataset and undertakes to maintain and update it, then they take on responsibility for that information and become the default authority behind its statements as described above. If, on the other hand, the institution accepts the data set and stores it without change as a closed resource, then it can be considered that the default authority remains the original steward like for any other scholarly document kept by the institution. |

||||

| References: | ||||

|

||||

| Modelling principles >> Extensions of CIDOC CRM |

||

Since the intended scope of the CIDOC CRM is a subset of the “real” world and is therefore potentially infinite, the model has been designed to be extensible through the linkage of compatible external type hierarchies. Of necessity, some concepts covered by the CIDOC CRM are defined in less details than others: E39 Actor and E30 Right, for example. This is a natural consequence of staying within the model’s clearly articulated practical scope in an intrinsically unlimited domain of discourse. These ‘underdeveloped’ concepts can be considered as candidate superclasses for compatible extensions, in particular for disciplines with a respective focus. Additions to the model are known as extensions while the main model is known as CRMbase. Compatibility of extensions with the CRM means that data structured according to an extension must also remain valid as instances of CIDOC CRM base classes. In practical terms, this implies query containment: any queries based on CIDOC CRM concepts to a KB should retrieve a result set that is correct according to the model’s semantics, regardless of whether the KR is structured according to the CIDOC CRM’s semantics alone, or according to the CIDOC CRM plus compatible extensions. For example, a query such as “list all events” should recall 100% of the instances deemed to be events by the CIDOC CRM, regardless of how they are classified by the extension. A sufficient condition for the compatibility of an extension with the CIDOC CRM is that its classes, other than E1 CRM Entity, subsume all classes of the extension, and all properties of the extension are either subsumed by CRM properties, or are part of a path for which a CIDOC CRM property is a shortcut, and that classes and properties of the extension can be well distinguished from those in the CIDOC CRM. For instance, a class “tangible object” may be in conflict with existing classes of the CIDOC CRM. Obviously, such a condition can only be tested intellectually. The CRM provides a number of mechanisms to ensure that coverage of the intended scope can be increased on demand without loosing compatibility:

Following strategies 1, 2 and 3 will have the result that the CIDOC CRM concepts subsume and thereby cover the extensions. This means that querying an extended knowledge base only with concepts of the CIDOC CRM will nevertheless retrieve all facts described via the extensions. In mechanism 3, the information in the notes is accessible in the respective knowledge base by retrieving the instances of E1 CRM Entity that are domain of P3 has note. Keyword search will also work for the content of the note. Rules should be applied to attach a note to the item most specific for the content. For instance, details about the role of an actor in an activity should be associated with the instance of E7 Activity, and not with the instance of E39 Actor. This approach is preferable when queries relating elements from the content of such notes across the knowledge base are not expected. In general, only concepts to be used for selecting multiple instances from the knowledge base by formal querying need to be explicitly modelled. This criterion depends on the expected scope and use of the particular knowledge base. The CIDOC CRM prioritizes modelling the kinds of facts one would like to retrieve and relate from heterogeneous content sources, potentially from different institutions. It does not, by way of contrast, focus on the modelling of facts with a more local scope such as the administrative practices internal to an institution. Mechanism 4, conservative extension, is more complex: With increasing use of the CIDOC CRM, there is also a need for extensions that model phenomena from a scope wider than the original one of the CIDOC CRM, but which are also applicable to the concepts that do fall within the CIDOC CRM’s scope. When this occurs, properties of the CIDOC CRM may be found to be applicable more generally to superclasses of the extension than to those of their current domain or range in the CIDOC CRM. This is a consequence of the key principle of the CIDOC CRM to model “bottom up”, i.e., selecting the domains and ranges for properties to be as narrow as they would apply in a well understood fashion in the current scope, thus avoiding making poorly understood generalizations at risk of requiring non-monotonic correction. The fourth mechanism for extending the CIDOC CRM by conservation extension can be seen to be split into two cases:

If case (2) should be documented and implemented in an extension module separate from the CIDOC CRM, it may come in conflict with the current way knowledge representation languages, such as RDF/OWL, treat it, because in formal logic changing the range or domain of a property is regarded as changing the ontological meaning completely; there is no distinction between the meaning of the property independent of domain and range and the specification of the domain and range. It is, however, similar to what in logic is called a conservative extension of a theory, and necessary for an effective modular management of ontologies. Therefore, for the interested reader, we describe here a definition of this case in terms of first order logic, which shows how modularity can formally be achieved: Let us assume a property P defined with domain class A and range class C also holds for a domain class B, superclass of A, and a range class D, superclass of C, in the sense of its ontological meaning in the real world. We describe this situation by introducing an auxiliary formal property P’, defined with domain class B and range class D, and apply the following logic: A(x) ⇒ B(x) C(x) ⇒ D(x) P(x,y) ⇒ A(x) P(x,y) ⇒ C(y) P’(x,y) ⇒ B(x) P’(x,y) ⇒ D(y) Then, P’ is a conservative extension of P if: A(x) ∧ C(y) ∧ P’(x,y) ⇔ P(x,y) In other words, a separate extension module may re-declare the respective property with another identifier, preferably using the same label, and implement the above rule. |

||

| Modelling principles >> Minimality |

||

Although the scope of the CIDOC CRM is very broad, the model itself is constructed as economically as possible:

A CIDOC CRM class is declared when:

|

||

| Modelling principles >> Monotonicity |

||

The CIDOC CRM’s primary function is to support the meaningful integration of information in an Open World. The adoption of the Open World principle means that the CIDOC CRM itself must remain fundamentally open and knowledge bases implemented using it should be flexible enough to receive new insights. At the model level, new classes and properties within the CIDOC CRM’s scope may be found in the course of integrating more documentation records or when new kinds of relevant facts come to the attention of its maintainers. At the level of the KBs, the need to add or revise information may arise due to numerous external factors. Research may open new questions; documentation may be directed to new or different phenomena; natural or social evolution may reveal new objects of study. It is the aim of the maintainers of the CIDOC CRM to respect the Open World principle and to follow the principle of monotonicity. Monotonicity requires that adding new classes and properties to the model or adding new statements to a knowledge base does not invalidate already modelled structures and existing statements. A first consequence of this commitment, at the level of the model, is that the CIDOC CRM aims to be monotonic in the sense of Domain Theory. That is to say, the existing CIDOC CRM constructs and the deductions made from them should remain valid and well-formed, even as new constructs are added by extensions to the CIDOC CRM. Any extensions should be, under this method, backwards compatible with previous models. The only exception to this rule arises when a previous construct is considered objectively incorrect by the domain experts and thus subjected to corrective revision. Adopting the principle of monotonicity has active consequences for the basic manner in which classes and properties are designed and declared in the CIDOC CRM. In particular, it forbids the declaration of complement classes, i.e., classes solely defined by excluding instances of some other classes. For example: FRBRoo (Bekiari et al (eds). 2015) extends the CIDOC CRM. In version 2.4 of FRBRoo, F51 Name Use Activity was declared as a subclass to the CIDOC CRM class E7 Activity. This class was added in order to describe a phenomenon specific to library practice and not considered within CRM base. F51 Name Use Activity describes the practice of an instance of E74 Group adopting and deploying a name within a context for a time-span. The creation of this extension is monotonic because no existing IsA relationship or inheritance of properties in CRM base are compromised and no future extension is ruled out. By way of contrast, if, to handle this situation, a subclass “Other Activity” had been declared, a non-monotonic change would have been introduced. This would be the case because the scope note of a complement class like “Other Activities” would forbid any future declaration of specializations of E7 Activity such as ‘Name Use Activity’. In the case the need arose to declare a particular specialized subclass, a non-monotonic revision would have to be made, since there would be no principled way to decide which instances of ‘Other Activity’ were instances of the new, specialized class and which were not. Such non-monotonic changes are extremely costly to end users, compromising backwards compatibility and long-term integration. As a second consequence, maintaining monotonicity is also required during revising or augmenting data within a CIDOC CRM compatible system. That is, existing CIDOC CRM instances, their properties and the deductions made from them, should always remain valid and well-formed, even as new instances, regarded as consistent by the domain expert, are added to the system. For example: If someone describes correctly that an item is an instance of E19 Physical Object, and later it is correctly characterized as an instance of E20 Biological Object, the system should not stop treating it as an instance of E19 Physical Object. This is achieved by declaring E20 Biological Object as subclass of E19 Physical Object. This example further demonstrates that the IsA hierarchy of classes and properties can represent characteristic stages of increasing knowledge about some item during the processes of investigation and collection of evidence. Higher level classes can be used to safely classify objects whose precise characteristics are not known in the first instance. An ambiguous biological object may, for example, be classified as only a physical object. Subsequent investigation can reveal its nature as a biological object. A knowledge base constructed with CIDOC CRM classes designed to support monotonic revision allows for seeking physical objects that were not yet recognized as biological ones. This ability to integrate information with different specificity of description in a well-defined way is particularly important for large-scale information integration. Such a system supports scholars being able to integrate all information about potentially relevant phenomena into the information system without forcing an over or under commitment to knowledge about the object. Since large scale information integration always deals with different levels of knowledge of its relevant objects, this feature enables a consistent approach to data integration. A third consequence, applied at the level of the knowledge base, is that in order to formally preserve monotonicity, when it is required to record and store alternative opinions regarding phenomena all formally defined properties should be implemented as unconstrained (many: many) so that conflicting instances of properties are merely accumulated. Thus, integrated knowledge can serve as a research tool for accumulating relevant alternative opinions around well-defined entities, whereas conclusions about the truth are the task of open-ended scientific or scholarly hypothesis building. For example: King Arthur’s basic life events are highly contested. Once entered in a knowledge base, he should be defined as an instance of E21 Person and treated as having existed as such within the sense of our historical discourse. The instance of E21 Person is used as the collection point for describing possible properties and existence of this individual. Alternative opinions about properties, such as the birthplace and his living places, should be accumulated without validity decisions being made during data compilation. King Arthur may be entered as a different instance, of E28 Conceptual Object, for describing him as mythological character and accumulating possibly mythological facts. The fourth consequence of monotonicity relates to the use of time dependent properties in a knowledge base. Certain properties declared in the CIDOC CRM, such as having a part, an owner or a location, may change many times for a single item during the course of its existence. Asserting that such a property holds for some item means that that property held for some particular, undetermined time-span within the course of its existence. Consequently, one item may be the subject of multiple statements asserting the instantiation of that property without conflict or need for revision. The collection of such statements would reflect an aggregation of these instances of this property holding over the time-span of the item’s existence. If a more specific temporal knowledge is required/available, it is recommended to explicitly describe the events leading to the assertion of that property for that item. For example, in the case of acquiring or losing an item, it would be appropriate to declare the related event class such as E9 Move. By virtue of this principle, the CRM achieves monotonicity with respect to an increase of knowledge about the states of an item at different times, regardless of their temporal order. Time-neutral properties may be specialized in a future monotonic extension by time-specific properties, but not vice-versa. Also, many properties registered do not change over time or are relative to events in the model already. Therefore, the CIDOC CRM always gives priority to modelling properties as time-neutral, and rather representing changes by events. However, for some of these properties many databases may describe a “current” state relative to some property, such as “current location” or “current owner”. Using such a “current” state means that the database manager is able to verify the respective reality at the latest date of validity of the database. Obviously, this information is non-monotonic, i.e., it requires deletion when the state changes. In order to preserve a reduced monotonicity, these properties have time-neutral superproperties by which respective instances can be reclassified if the validity becomes unknown or no longer holds. Therefore, the use of such properties in the CRM is only recommended if they can be maintained consistently. Otherwise, they should be reclassified by their time-neutral superproperties. This holds in particular if data is exported to another repository, see also the paragraph “Authorship of Knowledge Base Contents” |

||

| Modelling principles >> Disjointness |

||

Classes are disjoint if they cannot share any common instances at any time, past, present or future. That implies that it is not possible to instantiate an item using a combination of classes that are mutually disjoint or with subclasses of them (see “multiple instantiation” in section “Terminology”). There are many examples of disjoint classes in the CIDOC CRM. A comprehensive declaration of all possible disjoint class combinations afforded by the CIDOC CRM has not been provided here; it would be of questionable practical utility, and may easily become inconsistent with the goal of providing a concise definition. However, there are two key examples of disjoint class pairs that are fundamental to effective comprehension of the CIDOC CRM:

This page is left blank on purpose |

||

| Introduction to the basic concepts |

||

The following paragraphs explain the most general logic of the CIDOC CRM. The CIDOC CRM is a formalized representation of historical discourse, a formal ontology. In this capacity, it is meant to support the (re)presentation of fact based, analytic discourse about what has happened in the past in a human understandable and machine-processable manner. It achieves this function by proposing a series of formalized properties (relations) and classes. The formalized properties support the making of semantically explicit statements relating classes of things. Their formal definition logically explicates the classes of things to which they may pertain. The CIDOC CRM properties thus enable a formal, logically explicit description of relations between individual, real world items, classified under distinct ontological classes. Encoding analytic data pertaining to the past under such a system of statements provides a standard representation for data and allows the uniform application of reasoning to large sets of data. Grounding this high-level logic is a hierarchical system of classes and relations, that provide basic ontological distinctions by which to represent historical discourse. Familiarity with the basic ontological distinctions made in the top level of the class hierarchy provides the basic entry point to understanding how to apply the CIDOC CRM for knowledge representation. The highest-level distinction in the CIDOC CRM is represented by the top-level concepts of E77 Persistent Item, equivalent to the philosophical notion of endurant; E2 Temporal Entity, equivalent to the philosophical notion of perdurant and, further, the concept of E92 Spacetime Volume. As an event-centric model, supporting historical discourse, the CIDOC CRM firstly enables the description of entities that are themselves time-limited processes or evolutions within the passing of time using E2 Temporal Entity and its subclasses. Their basic function is to capture the fact of something having happened over time. In addition to allowing the description of a temporal duration, the subclasses of E2 Temporal Entity are used to document the historical relations between objects, similar to the role of action verbs in a natural language phrase. The more specific subclasses of E2 Temporal Entity enable the documentation of events pertaining to individually related/affected material, social or mental objects that have been described using subclasses of E77 Persistent Item. This precise documentation is enabled through the use of specialized properties formalizing the manner of the relation or affect. Examples of specific subclasses of E2 Temporal Entity include E12 Production, which allows the representation of events of making things by humans, and E5 Event which allows the documentation, among other things, of geological events and large-scale social events such as a war. Each of these subclasses have specific properties associated to them which allow them to function to represent the specific, real world connection between instances of E77 Persistent Item, such as the relation of an object to its time of production through P108 was produced by (E12) or the relation of a place to a geological phenomenon through P7 was place of (E5). The entities that E2 Temporal Entity documents, being time limited processes / occurrences, are such that their existence can be declared only on the basis of direct observation or recording of the event, or indirect observation of its material outcomes. Evidence of such entities may be preserved on material objects that are permanently changed because of them. Likewise, events may have been recorded in text or remembered through oral history. E2 Temporal Entity and its subclasses are central to the CRM and essential for almost all modelling tasks (e.g., in a museum catalogue one cannot consider an object outside its production event). The real-world entities, which the event centric modelling of the CIDOC CRM aims to enable the accurate historical description of, are captured through E77 Persistent Item and its subclasses. E77 Persistent Item is used to describe entities that are relatively stable in form through the passage of time, maintaining a recognizable identity because their significant properties do not change. Specific subclasses of E77 Persistent Item can illustrate this point. E22 Human Made Object is used for the description of discrete, physical objects having been produced by human action, such as an artwork or monument. An artwork or monument is persistent with regards to its physical constitution. So long as it retains its general physical form, it is said to exist and to participate in the flow of historical events. E28 Conceptual Object is also used to describe persistent items, but of a mental character. It is used to describe identifiable ideas that are named and form an object of historical discourse. Its identity conditions rely in having a carrier by which it can be recalled. The entities described by E77 Persistent Item are prone to change through human activity, biological, geological or environmental processes, but are regarded to continue to exist and be the same just as long as such changes do not alter their basic identity (essence) as defined in the scope note of the relevant class. The notion of identity is key in the application of CIDOC CRM. The properties and relations it provides are designed to allow the accurate historical description of the evolution of real-world items through time. This being the case, classes and properties are created in order to provide a definition, which will allow the accurate application of the classes or properties to the same real-world items by diverse users. Identity, in the sense of the CIDOC CRM, therefore, means that informed people are able to agree that they refer to the same, single thing in its distinction from others, both in its extent and over its time of existence. The criteria for such a determination should come from understanding the scope note of the respective CIDOC CRM class this thing is regarded to be an instance of, because communication via information systems may not leave space for respective clarifying dialogues between users. For example, the Great Sphinx of Giza may have lost part of its nose, but there is no question that we are still referring to the same monument as that before the damage occurred, since it continues to represent significant characteristics and distinctness from an overall shaping in the past, which is of archaeological relevance. Things lacking sufficient stability or differentiation, such as atmosphere, soil, clouds, waves, are not instances of E77 Persistent Item, and not suited for information integration. Discourse about such items may be documented with concepts of the CIDOC CRM as observations in relation to things of persistent identity, such as places. Learning to distinguish and then interrelate instances of E77 Persistent Item (endurants) and instances of E2 Temporal Entity (perdurants) using the appropriate properties is key to the proper understanding and application of CIDOC CRM in order to formally represent analytic historical data. In the large majority of cases, the distinction this provides, and the subsequent elaboration of subclasses and properties is adequate to describe the content of database records in the cultural and scientific heritage domain. In exceptional cases, where we need to consider complex combinations of changes of spatial extent over time, the concept of spacetime (E92 Spacetime Volume) also needs to be considered. E92 Spacetime Volume describes the entities whose substance has or is an identifiable, confined geometrical extent in the material world that may vary over time, fuzzy boundaries notwithstanding. For example, the built settlement structure of the city of Athens is confined both from the point of view of time-span (from its founding until now) and from its changing geographical extent over the centuries, which may become more or less evident from current observation, historical documents and excavations. Even though E92 Spacetime Volume is an important theoretical part of the model, it can be ignored for most practical documentation and modelling tasks. The key to the proper understanding of CIDOC CRM comes through the appropriation of its basic divisions and the logic these represent. It is important to underline that the CIDOC CRM is not intended to function as a classification system or vocabulary tool. The basic class divisions in CIDOC CRM are declared in order to be able to apply distinct properties to these classes and, in so doing, formulate precise, analytic propositions that represent historical realities. The expressive power of CIDOC CRM comes not from the application of classes to classify entities but in the documenting the interrelation of individual historical items through well-defined properties. These properties characteristically cover subjects such as relations of identifying items by names and identifiers; participation of persistent items in temporal entities; location of temporal entities and physical things in space and time; relations of observation and assessment; part-decomposition and structural properties of anything; influence of things and experiences on the activities of people and their products; reference of information objects to anything. We explain these concepts with the help of graphical representations in the next sections. |

||

| Introduction to the basic concepts >> Relations with Events |

||

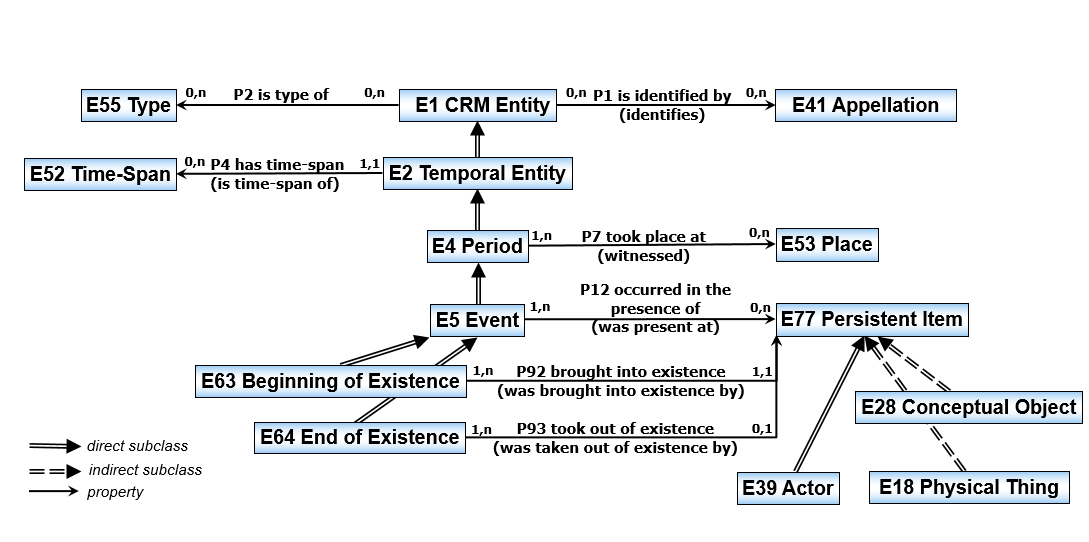

Figure 1 illustrates the minimal properties in the CIDOC CRM for documenting “what has happened”, the central pattern of the Model. Let us first consider the class E1 CRM Entity, the formal top class of the model. It primarily serves a technical purpose to aggregate the ontologically meaningful concepts of the model. It declares however two important properties of general validity and distinct features of the Model: P1 is identified by, with range E41 Appellation, makes the fundamental ontological distinction between the identity of a particular and an identifier (see section “Reality, Knowledge Bases and CIDOC CRM” above), and in practice allows for describing a discourse about resolving historical ambiguities of names and reconciliation of multiple identifiers. The property P2 has type, with range E55 Type, constitutes a practical interface for refining classes by terminologies, being often volatile, as detailed in the section “About Types” below.

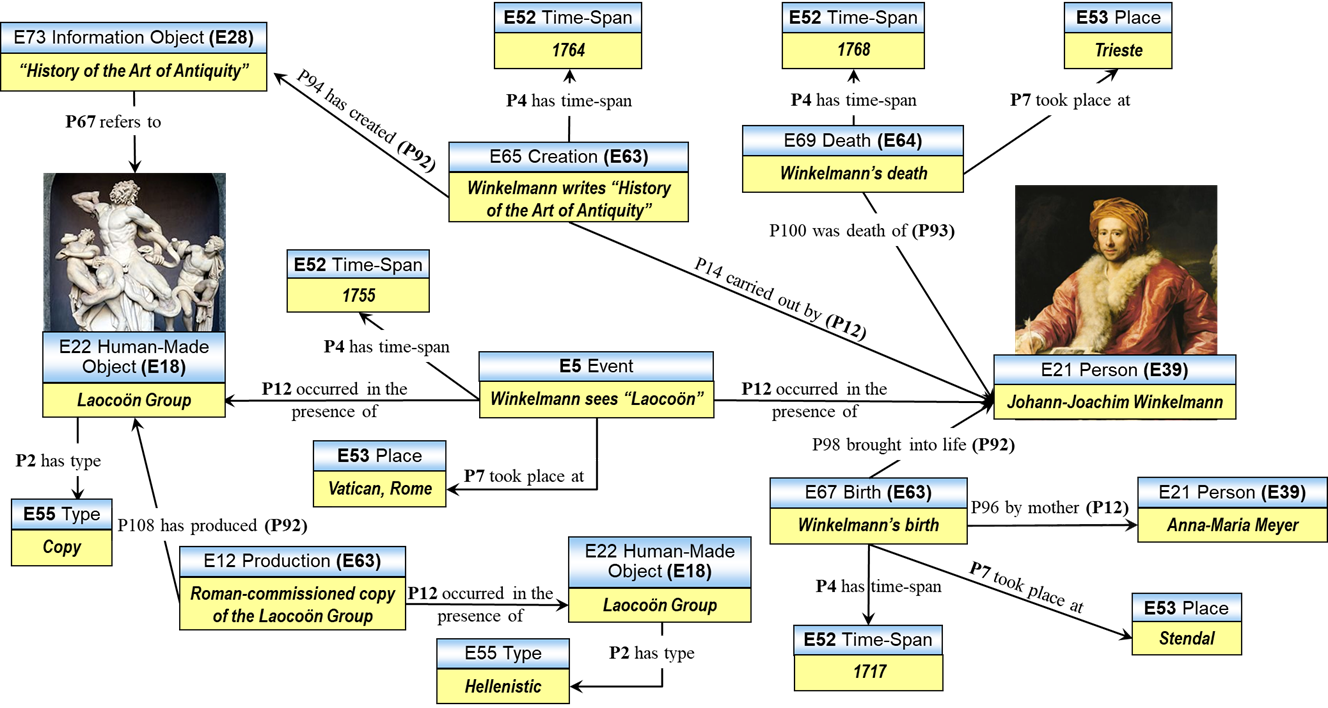

Figure 1: High Level Properties and Classes of CIDOC CRM All classes in figure 1 are direct or indirect subclasses of E1 CRM Entity, but for better readability, only the “subclass of” -link from E2 Temporal Entity is shown. The latter comprises phenomena that continuously occur over some time-span (E52 Time-Span) in the natural time dimension, but some of them may not be confined to specific area, such as a marriage status. Further specializing, E4 Period comprises phenomena occurring in addition within a specific area in the physical space, which can be specified by P7 took place at, with range E53 Place. Instances of E4 Period can be of any size, such as the Warring States Period, the Roman Period, a siege or just the process of making a signature. Further specializing, E5 Event comprises phenomena involving and affecting certain instances of E77 Persistent Item in a way characteristic of the kind of process, which can be specified by the property P12 occurred in the presence of. This concept of presence is very powerful: It constrains the existence of the involved things to the respective places within the specified time and implies the potential of passive or active involvement and mutual impact. Via presence, events represent nodes in a network of things meeting in various combinations in the course of time at different places. The most important specializations of E77 Persistent Item in this context are: E39 Actor, those capable of intentional actions, E18 Physical Thing, having an identity bound to a relative stability of material form, and E28 Conceptual Object, the idealized things that can be recognized but have an identity independent from the materialization on a specific carrier. The property P12 occurred in the presence of has 36 direct and indirect subproperties, relating these and many more subclasses of E5 Event and E77 Persistent Item. Regardless whether a CRM-compatible knowledge base is created with these properties only or with their much more expressive specializations, querying for the above presented five properties will provide answer to all “Who-When-Where-What-How” questions, and allow for retrieving potentially richly elaborated stories of people, places, times and things. This pattern of “meeting” is complemented by two more subclasses of E5 Event: E63 Beginning of Existence and E64 End of Existence, which imply not only presence, but constitute the endpoints of existence of things and people in space and time, often in explicit presence and interaction with others, be they causal by producing or consuming or just witnessing. Note that the Model supports multiple instantiation. As a consequence, particular events can be instances of combinations of these and others classes, describing tightly integrated processes of multiple nature. The representation of things connected in events by presence, beginning and end of existence is sufficient to describe the logic of termini postquos and antequos, a major form of reasoning about chronology in historical studies. Example: As a simple, real example of applying the above concepts we present a historical event, relevant for the history of art: Johann-Joachim Winkelmann (a German Scholar) has seen the so-called Laocoön Group in 1755 in the Vatican in Rome (at display in the Cortile del Belvedere). He described his impressions in 1764 in his “History of the Art of Antiquity”, (being the first to articulate the difference between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art, characterizing Greek art with the famous words “…noble simplicity, silent grandeur”). The sculpture, in Hellenistic "Pergamene baroque" style (Bieber 1961, Brilliant 2000) is widely assumed to be a copy, made between 27 BC and 68 AD (following a Roman commission) from a Greek (no more extent) original. Johann-Joachim Winkelmann was born 1717 as child of Martin Winkelmann and Anna-Maria Meyer and died in 1768 in Trieste. Figure 2 presents a semantic graph of this event, as described above, using CIDOC CRM concepts. The facts in parentheses above are omitted for better clarity. Instances of classes are represented by informative labels instead of identifiers, in boxes showing the class label above the instance label. Properties are represented as arrows with the property label attached. After class labels and property labels, we show in parenthesis the identifiers of the respective superclasses and superproperties from figure 1, in order to demonstrate that the story can be represented and queried with these concepts only. It also shows how concept specialization increases expressiveness without losing genericity. It is noteworthy that the transfer of information from the Greek original, to the copy, to the mind of Winkelmann and into his writings can be solely understood by this chain of things being present in different meetings. Note also that the degree to which a fact is believed to be real does not affect the choice of CIDOC CRM concepts for description of the fact, nor the reality concept underlying the Model.

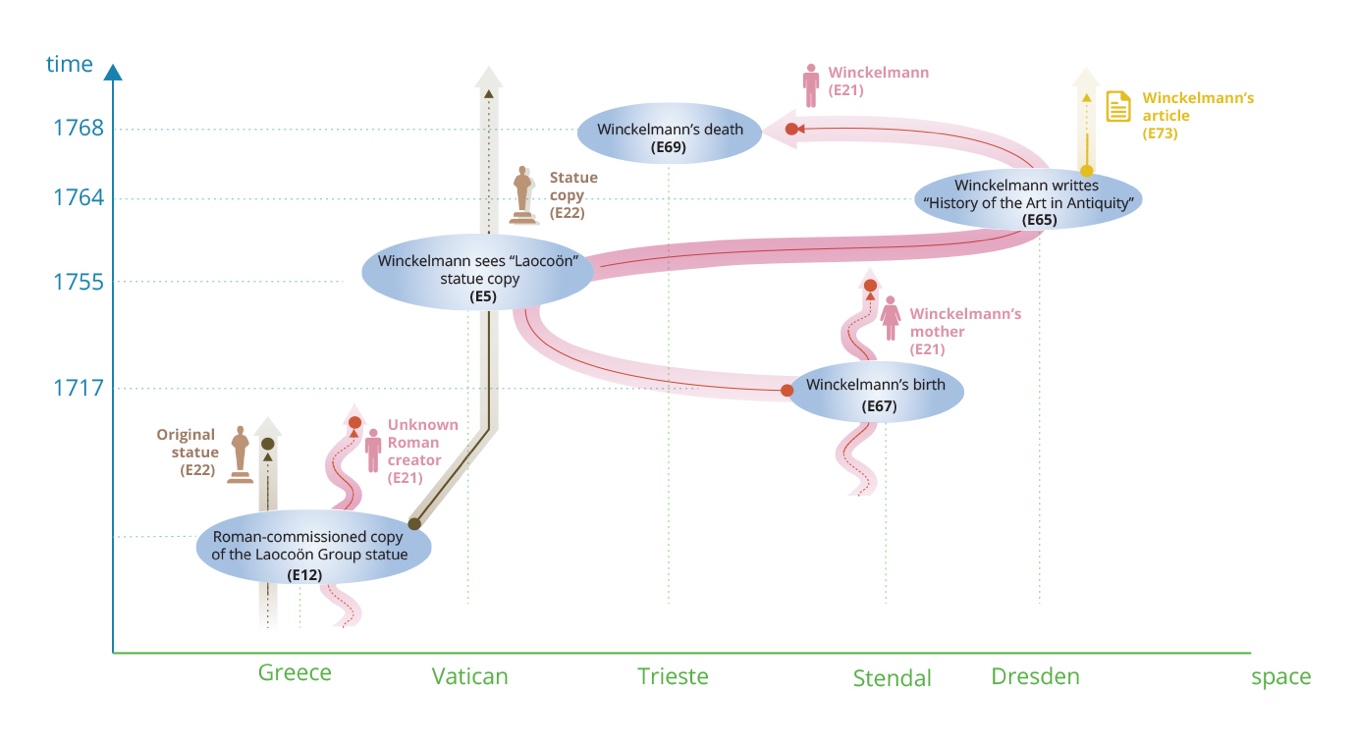

Figure 2: CIDOC CRM Encoding Example (Winkelmann seeing Laocoön) Figure 2 represents in addition one more top-level property of the CIDOC CRM: P67 refers to, which describe an evidence-based fact that an information object makes reference to an identifiable item. As mentioned above, the central concept of the CIDOC CRM is the representation of a part of reality that can be approximated as a network of things meeting in various combinations in spacetime. Using the same example from above, figure 3 illustrates this concept via an alternative symbolic representation. It aims at rendering the idea that people and things in the past have performed mostly unknown trajectories in spacetime and the historical facts known to us constrain their possible whereabouts for some limited time-spans to having been together at some known or unknown place. We use a one-dimensional representation of space, as used in archaeology to describe the spatial evolution of periods or cultures over time, and a vertical time axis. We symbolize the trajectories of things and people as fuzzy lines between events in order to render their relative indeterminacy between known events. Non-animate things use to be stationary if not transferred, whereas people may move around on their own. We symbolize events as fuzzy ovals to render the fuzzy boundaries of events in space and time. Note that in this representation, as a general pattern, things may “survive” events, emerge from events or end in events. Beginning and ending of existence impose an additional temporal order on events of causal nature, which can be stronger than explicit dates. We symbolize the unreported ends of existence of people and things, which are also events, by a dot at the end of the trajectory. Figure 3: Symbolic Representation of "Winkelmann seeing Laocoön" as an Evolution in Space and Time In the following, we give an overview of the system of spatial and temporal relations in the CIDOC CRM, because it constitutes an important tool for precise documentation of the past and has a certain complexity that needs to be understood in a synopsis. |

||

| Relations with Events >> Spatial Relations |

||

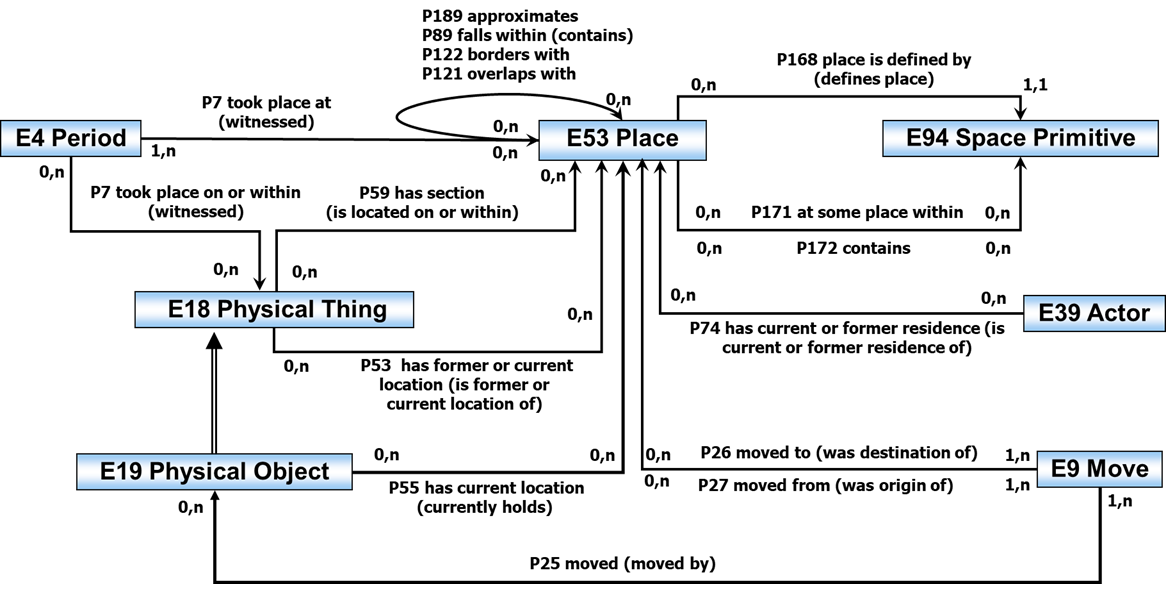

A major area of documentation and historical research centres around positioning in space of what has happened and the things involved, as well as reasoning about respective spatial relations. The key class CIDOC CRM provides for modelling this information is E53 Place. E53 Place is used to document geometric extents in the physical space containing actual or possible positions of things or happenings. The higher-level properties and classes of CIDOC CRM that centre around E53 Place allow for the documentation of: relations between places; recording the geometric expressions defining or approximating a place and their semantic function; tracing the history of locations of a physical object; identifying the places where an individual or group have been located; identifying places on a physical object and the spatial extent of certain temporal entities. Geometric Expressions of Place: Contemporary documentation of spatial information has access to advanced equipment for accurately recording location and libraries of georeferenced place information. For this reason, documentation of place now often includes the recording of precise coordinates for a referenced place. Of great importance semantically, is to understand the manner in which such a geometric place expression actually relates to a referenced place. The cluster or relations P168 place is defined by, P171 at some place within, and P172 contains allows the user to link to geometric place expressions while also accurately indicating how this expression relates to the documented place. Geometric place expressions are instances of E94 Space Primitive, a primitive class for expressing values in data systems not further analyzed in the CIDOC CRM. These properties provide a valid interface to the OGC standards, as elaborated in CRMgeo (Doerr & Hiebel 2013).

Figure 4: Basic CIDOC CRM Properties and Classes for Reasoning about Spatial Information Relations between Places: The cluster of relations P89 falls within (contains), P122 borders with, P121 overlaps with and P189 approximates can express relative relationships held between places. These properties hold between instances of E53 Place and allow interordering places using common mereotopological concepts. History of Object Locations: Instances of place are often referenced in order to record the location of some object. When the movement of the object to different locations through time is of interest, it is also important to be able to analytically record the different locations at which an object was and at what point. The CIDOC CRM offers two top level mechanisms for tracing the relation of objects to places. If the aspect of time is unknown or not of interest, then an object can be related to a place through the properties P53 has former or current location and P55 has current location. The former property is the conservatively appropriate choice for documenting the object-to-place relation when time elements are not known. If one is actively tracking current location, the latter property is also of use. When an accurate history of the temporal aspect of location should be provided, the user should take advantage of the class E9 Move, a temporal entity class. Instantiating E9 Move allows the user to document the origin, destination and concerned object of a move event using the collection of properties P27 moved from, P26 moved to, P25 moved. Being a temporal class E9 Move further allows the tracing of time, agency etc. Note that things may be moved indirectly as parts of or within other things. Actor Locations: Tracking the history of the location of actors is related to the history of object location with a significant difference: in the CIDOC CRM an actor is defined as an entity featuring agency which is not the case in objects and physical entities in general. Not being physical, an actor cannot be the subject of an instance of E9 Move which documents physical relocations. The CIDOC CRM thus offers the notion of P74 has current or former residence in order to document the relation of a person or group to a location as residing there at some time. Places on a Physical Object: In the recording of cultural heritage and other scientific data, particularly about mobile objects, including ships, it is often necessary to identify where on an object or a certain feature is located and where a certain phenomenon is observed. For this the CIDOC CRM offers the relation P59 has section relating the object to the places which are defined upon it. Note that Earth is the physical object we relate places to per default. In geological times, a narrower relation to a tectonic plate may be necessary. Spatial Extent of Temporal Entities: In order to spatially define the extent of temporal phenomena, the CIDOC CRM offers two properties that apply to all instances of temporal entity under the class E4 Period: P7 took place at and P8 took place on or within. The former is used to relate a temporal phenomenon directly to an instance of E53 Place which provides the geometric context in which that phenomenon took place. The latter property allows the documentation of a temporal phenomenon taking place in relation to a physical object. This is useful for recording information such as the occurrence of an event on a moving ship or within a particular storage container, where the geometric location is not known or indirectly relevant. |

||

| Relations with Events >> Temporal Relations |

||

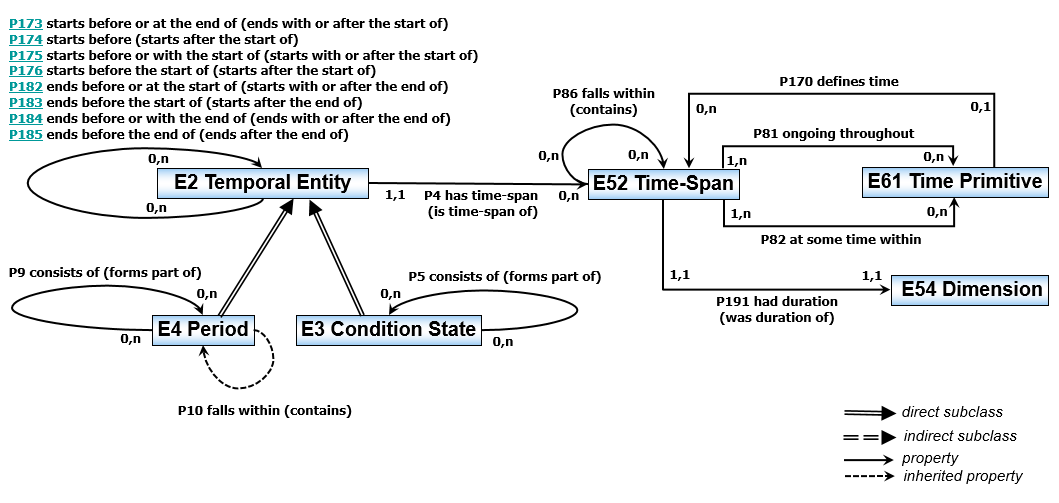

Historical and scientific discourse about the past deals with different levels of knowledge regarding events and their temporal ordering that feed into chronology. Chronology is fundamental to understanding social and natural history, and reasoning about temporal relations and causality is directly related. An immense wealth of physical observations allows for inferring temporal relations and vice-versa. It is important to be able to document temporality both with regards to known dates but also according to relative positioning within a historical time line. The top-level properties of the CIDOC CRM relating to temporal entities support the documentation of: dates as time spans or dimensions, mereological relations between temporal entities as well as a complete suite of topological relations. Dates and Durations: When some absolute dates limiting a temporal entity are known, this can be documented by instantiating the P4 has time-span property and creating an instance of E52 Time-span. Dates should then be recorded as instances of E61 Time Primitive and related to the time-span through properties P81 ongoing throughout or P82 at some time within. Time is recorded as a span and not an instant in the CIDOC CRM. The choice of property P81 ongoing throughout allows the documentation of knowledge that a temporal phenomenon was occurring at least at all points of a known time span. The property P82 at some time within allows the weaker claim that the phenomenon must have occurred within the limits of a particular time span without further specifying as to when precisely. It is the default for historical dates, given, for instance, in years for events of much smaller duration. The actual mode of encoding the documented date is outside the scope of the CIDOC CRM, which defines this with a primitive class, E61 Time Primitive. Finally, the property P191 had duration can be deployed in order to document a temporal phenomenon with known duration but with less precisely temporal positioning. For instance, a birth may be known with the precision of a year, but with a duration of 3 hours. For documenting exact time-spans that are result of a declaration rather than observation, for instance in order to describe a time-span multiple events may fall into, the property P170 defines time allows for specifying the time-span uniquely by a temporal primitive, rather than by P81 ongoing throughout or P82 at some time within using an identical time primitive. Figure 5: Basic CIDOC CRM Properties and Classes for Reasoning about Temporal Information Mereological relations: The documentation of the part-whole relationship of temporal phenomena is crucial for historical reasoning. The CIDOC CRM distinguishes under temporal entities two immediate specializations: E4 Period is a high-level concept for the documentation of temporal phenomena of change and interactions in space and time, comprising but not limited to historical periods such as Ming or Roman, and is further specialized in rich hierarchy of more specific processes and activities. The second specialization is E3 Condition State, a rather specific class for the documentation of static phases of physical things. The CIDOC CRM so far does not describe a higher-level class of static phases, because they are normally deductions from multiple observations, problematic in information integration and vulnerable to non-monotonic revision. For both classes, two different mereological relations are articulated: The property P9 consists of is used to document proper parthood between instances of E4 Period, i.e., to describe how the phenomena that make up an instance of E4 Period can causally be subdivided into more delimited phenomena. In contrast, the property P10 falls within, explained further in the section about spatiotemporal relations, describes only a non-causal co-occurrence in the same spatiotemporal extent. The property P5 consists of indicates, in analogy, proper parthood between instances of E3 Condition State. Topological Relations: A lot of semantic relations have implications on the temporal ordering of temporal entities. For instance, meeting someone must occur after birth and before death of the involved parties. Information can only be transferred after it has been learned. On the other side, direct information about temporal order has implications on possible or impossible semantic relations. This form of reasoning is of paramount importance for research about the past. It turned out that the popular temporal relations defined by (Allen, 1983), which the CIDOC CRM had adopted in previous versions, are not well suited to describe inferences from semantic relations, as detailed in the section “Temporal Relation Primitives based on fuzzy boundaries” below. Instead, the CIDOC CRM introduces a theory of fuzzy boundaries in time that enables the accurate interpositioning of temporal entities between themselves taking into account the inherent fuzziness of temporal boundaries. This model subsumes the earlier introduced Allen temporal relations which may continued to be used in extensions of the CIDOC CRM. |

||

| Relations with Events >> Spatiotemporal Relations |

||||

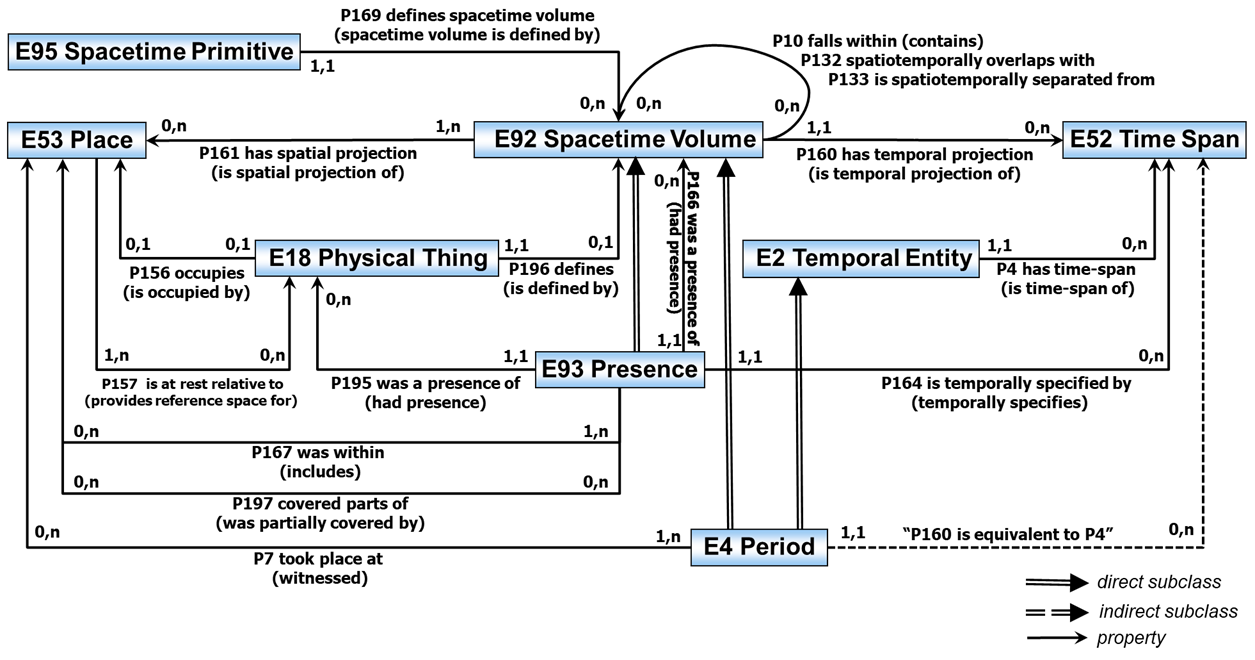

Treating space and time as separate entities is normally adequate for describing events and where things are. When more precise documentation and reasoning is required about phenomena spreading out over time, such as Bronze Age, a settlement, a nation, moving reference frames such as ships, things being stored in containers and moved around, built structures being partially destroyed, rebuilt and altered etc., space and time must be understood as a coherent continuum, the so-called spacetime. This is not a familiar concept for many users, and those not interested in such details may therefore skip this section. However, the respective model the CIDOC CRM adopts constitutes a valid interface to the OGC standards, as elaborated in CRMgeo (Doerr & Hiebel 2013) and important for connecting to GIS applications. The key class CIDOC CRM provides for modelling this information is E92 Spacetime Volume. E92 Spacetime Volume is used to document geometric extents in the physical spacetime containing actual or possible positions of things or happenings, in particular in those cases when the changes of place to be documented cannot be reduced to distinct events, because the spatial extent changes continuously. The higher-level properties and classes of CIDOC CRM that centre around E92 Spacetime Volume allow for the documentation of: relations between spacetime volumes, relations to space and time as separate entities, and treating the exact extent of physical things and periods in space at any time of their existence as spacetime volumes. Its use is particularly elegant for the description of temporal gazetteers. Defining a Spacetime Volume: There are three ways to define a spacetime volume:

Figure 6: Basic CIDOC CRM Properties and Classes for Reasoning with Spacetime Volumes Relations with Places and Physical Things: The property P161 has spatial projection associates a spacetime volume with the complete spatial extent it has occupied during its time-span of definition. Due to relativity of space, the definition of an instance of E53 Place must be relative to some physical thing as geometric reference. This can explicitly be documented with the property P157 is at rest relative to. If the place where something is at a certain point in time is given in multiple reference spaces in relative movement, such as with respect to a ship versus to the seafloor, these differently defined places may later move apart. Therefore, a spacetime volume, even though uniquely defined, can have any number of spatial projections, depending on the reference space. Currently, the GPS system defines a default reference space on the surface of Earth. In art conservation and other descriptions of mobile object of fixed shape, it is useful to refer to the precise place a physical thing occupies with respect to itself as reference space via P156 occupies, for further analysis. P156 occupies constitutes a particular projection of the spacetime volume of this thing. In contrast, the property P53 has former or current location only describes that a thing was within a specific place given in some reference space for an undefined time. Relations with Time-Spans and Periods: The property P160 has temporal projection associates a spacetime volume with the complete temporal extent it has covered comprising all places of its definition. In contrast to places, the reference system of time is unique[8] except for the choice of origin. For instances of E4 Period and its subclasses, which inherit P160 has temporal projection, the property is actually identical with the property P4 has time span inherited from E2 Temporal Entity, because is describes the temporal extent of the phenomena that make up an instance of E4 Period. Therefore, it is recommended to use P4 has time span for instances of E4 Period and its subclasses, rather than P160 has temporal projection. Relations of Presence: Instances of E93 Presence are specialized instances of E92 Spacetime Volume that are identical with the spatial evolution of a larger spacetime volume specified by P166 was presence of, but delimited to a, normally short, time-span declared by P164 is temporally specified by. In other words, they constitute “snapshots” or “time-slices” of another spacetime volume, such as the extent of the Roman Empire during 30AD. They are the basic construct to describe exactly where something was or happened at a particular time (-span), in connection with the property P161 has spatial projection. In particular, it allows for describing the whereabouts of mobile objects, be it in the storage of a museum, a palace, deposited in the ground, or transported in a container, such as the bone of a saint. For ease of use, a shortcut P195 was presence of is defined directly to E18 Physical Thing, bypassing the definition of its spacetime volume. Topological Relations: Finally, the Model defines truly spatiotemporal topological relations. P10 falls within (contains) is the complete inclusion of one spacetime volume in another. It should not be confused with inclusion in the spatial and temporal projection, which may be larger. E.g., in 14 AD, Mesopotamia was not within the Roman Empire. Further, the properties P132 spatiotemporally overlaps with and its negation P133 is spatiotemporally separated from are fundamental to argue about temporary parthood, possible continuity etc. |

||||

| References: | ||||

|

||||

| Introduction to the basic concepts >> Specific Modelling Constructs |

||

| Specific Modelling Constructs >> About Types |

||

Virtually all structured descriptions of museum objects begin with a unique object identifier and information about the "type" of the object, often in a set of fields with names like "Classification", "Category", "Object Type", "Object Name", etc. All these fields are used for terms that declare that the object belongs to a particular category of items. In the CIDOC CRM the class E55 Type comprises such terms from thesauri and controlled vocabularies used to characterize and classify instances of CIDOC CRM classes. Instances of E55 Type represent concepts (universals) in contrast to instances of E41 Appellation, which are used to name instances of CIDOC CRM classes. For this purpose, the CIDOC CRM provides two basic properties that describe classification with terminology, corresponding to what is the current practice in the majority of information systems. The class E1 CRM Entity is the domain of the property P2 has type (is type of), which has the range E55 Type. Consequently, every class in the CIDOC CRM, with the exception of E59 Primitive Value, inherits the property P2 has type (is type of). This provides a general alternative mechanism to specialize the classification of CIDOC CRM instances to any level of detail, by linking to external vocabulary sources, thesauri, classification schemas or ontologies. Analogous to the function of the P2 has type (is type of) property, some properties in the CIDOC CRM are associated with an additional property. These are numbered in the CIDOC CRM documentation with a ‘.1’ extension. The range of these properties of properties always falls under E55 Type. The purpose of a property of a property is to provide an alternative mechanism to specialize its domain property through the use of property subtypes declared as instances of E55 Type. They do not appear in the property hierarchy list but are included as part of the property declarations and referred to in the class declarations. For example, P62.1 mode of depiction: E55 Type is associated with E24 Physical Man-made Thing. P62 depicts (is depicted by): E1 CRM Entity. The class E55 Type also serves as the range of properties that relate to categorical knowledge commonly found in cultural documentation. For example, the property P125 used object of type (was type of object used in) enables the CIDOC CRM to express statements such as “this casting was produced using a mould”, meaning that there has been an unknown or unmentioned object, a mould, that was actually used. This enables the specific instance of the casting to be associated with the entire type of manufacturing devices known as moulds. Further, the objects of type “mould” would be related via P2 has type (is type of) to this term. This indirect relationship may actually help in detecting the unknown object in an integrated environment. On the other side, some casting may refer directly to a known mould via P16 used specific object (was used for). So, a statistical question to how many objects in a certain collection are made with moulds could be answered correctly (following both paths through P16 used specific object (was used for) - P2 has type (is type of) and P125 used object of type (was type of object used in). This consistent treatment of categorical knowledge enhances the CIDOC CRM’s ability to integrate cultural knowledge. Types, that is, instances of E55 Type and its subclasses, can be used to characterize the instances of a CIDOC CRM class and hence refine the meaning of the class. A type ‘artist’ can be used to characterize persons through P2 has type (is type of). On the other hand, in an art history application of the CIDOC CRM it can be adequate to extend the CIDOC CRM class E21 Person with a subclass E21.xx Artist. What is the difference of the type ‘artist’ and the class Artist? From an everyday conceptual point of view there is no difference. Both denote the concept ‘artist’ and identify the same set of persons. Thus, in this setting a type could be seen as a class and the class of types may be seen as a metaclass. Since current systems do not provide an adequate control of user defined metaclasses, the CIDOC CRM prefers to model instances of E55 Type as if they were particulars, with the relationships described in the previous paragraphs. Users may decide to implement a concept either as a subclass extending the CIDOC CRM class system or as an instance of E55 Type. A new subclass should only be created in case the concept is sufficiently stable and associated with additional explicitly modelled properties specific to it. Otherwise, an instance of E55 Type provides more flexibility of use. Users that may want to describe a discourse not only using a concept extending the CIDOC CRM but also describing the history of this concept itself, may choose to model the same concept both as subclass and as an instance of E55 Type with the same name. Similarly, it should be regarded as good practice to foresee for each term hierarchy refining a CIDOC CRM class a term equivalent of this class as top term. For instance, a term hierarchy for instances of E21 Person may begin with “Person”. One role of E55 Type is to be the CIDOC CRM’s interface to domain specific ontologies and thesauri or less formal terminological systems. Such sets of concepts can be represented in the CIDOC CRM as subclasses of E55 Type, forming hierarchies of terms, i.e., instances of E55 Type linked via P127 has broader term (has narrower term). Such hierarchies may be extended with additional properties. Other standard models, in particular richer ones, used to describe terminological systems can also be interfaced with the CIDOC CRM by declaring their respective concept class as being equivalent to E55 Type, and their respective broader/narrower relation as being identical with P127 has broader term (has narrower term), as long as they are semantically compatible. In addition to being an interface to external thesauri and classification systems, E55 Type is an ordinary class in the CIDOC CRM and a subclass of E28 Conceptual Object. E55 Type and its subclasses inherit all properties from this superclass. Thus, together with the CIDOC CRM class E83 Type Creation the rigorous scholarly or scientific process that ensures a type is exhaustively described and appropriately named can be modelled inside the CIDOC CRM. In some cases, particularly in archaeology and the life sciences, E83 Type Creation requires the identification of an exemplary specimen and the publication of the type definition in an appropriate scholarly forum. This is very central to research in the life sciences, where a type would be referred to as a “taxon,” the type description as a “protologue,” and the exemplary specimens as “original element” or “holotype”. Finally, instances of E55 Type or suitable subclasses can describe universals from type systems not organized in thesauri or ontologies, such as industrial product names and types, defined and published by the producers themselves for each new product or product variant. |

||

| Specific Modelling Constructs >> Temporal Relation Primitives based on fuzzy boundaries |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

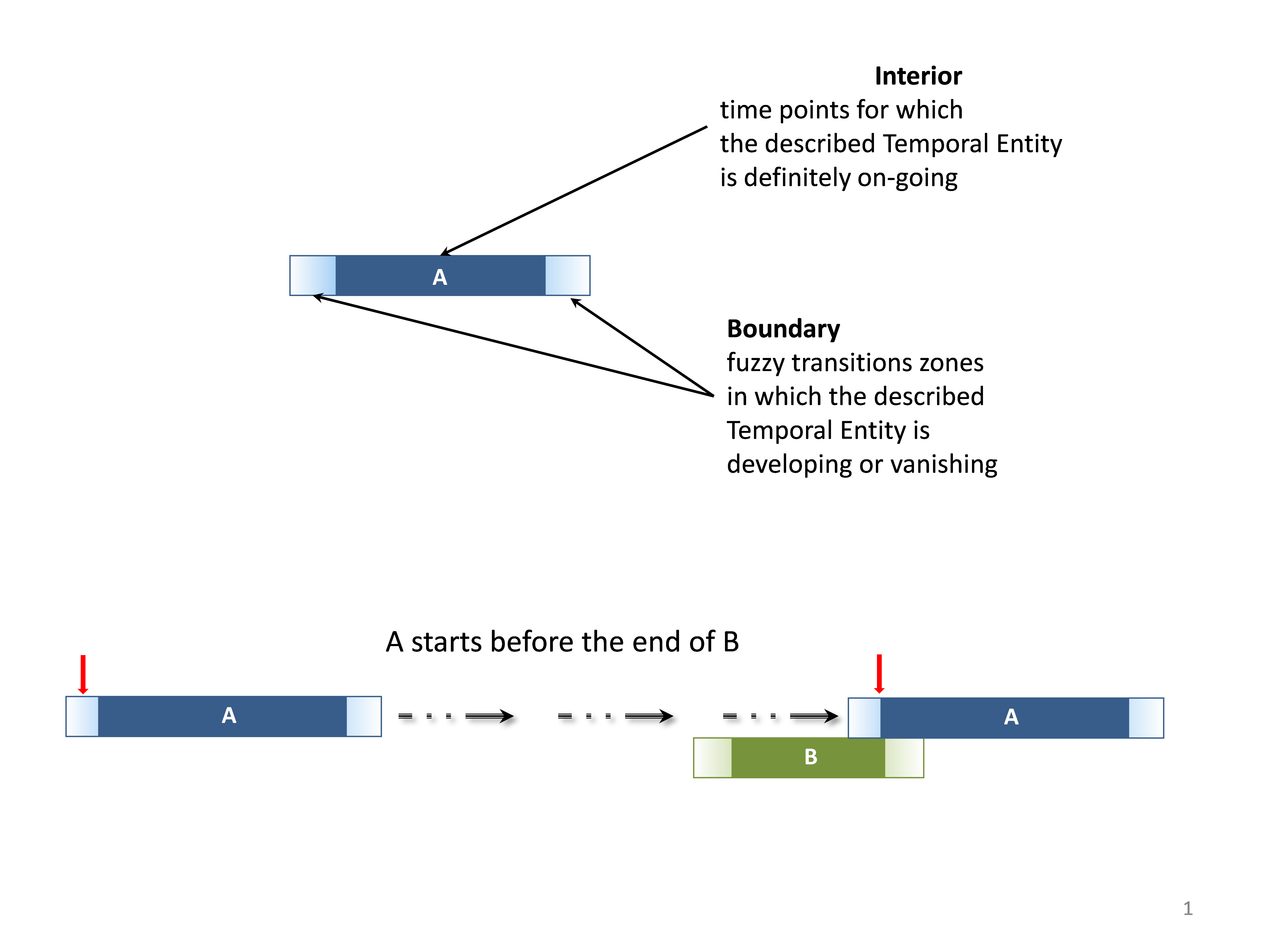

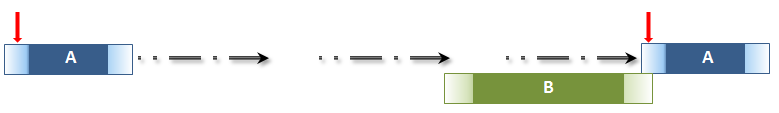

It is characteristic for sciences dealing with the past, such as history, archaeology or geology, to derive temporal topological relations from stratigraphic and other observations and from considerations of causality between events. For this reason, the CIDOC CRM introduced in version 3.3 the whole set of temporal relationships of Allen’s temporal logic (the now deprecated properties P114 to P120). It was regarded at that time as a well-justified, exhaustive and sufficient theory to deal with temporal topological relationships of spatiotemporal phenomena relevant to cultural historical discourse. Allen’s temporal logic is based on the assumption of known, exact endpoints of time intervals (time-spans), described by an exhaustive set of mutually exclusive relationships. Since many temporal relations can be inferred from facts causal to them, e.g., a birth necessarily occurring before any intentional interaction of a person with other individuals, or from observations of material evidence without knowing the absolute time, the temporal relationships pertain in the CIDOC CRM to E2 Temporal Entities, and not their Time-Spans, which require knowledge of absolute time. If absolute times are known, deduction of Allen’s relation is a simple question of automated calculus and not the kind of primary scientific insight the CIDOC CRM, as a core model, is interested in. However, their application turned out to be problematic in practice for two reasons: Firstly, facts causal to temporal relationships result in expressions that often require a disjunction (logical OR condition) of Allen’s relationships. For instance, a child may be stillborn. Ignoring states at pregnancy as it is usual in older historical sources, birth may be equal to death, meet with death or be before death. The knowledge representation formalism chosen for the CIDOC CRM however does not allow for specifying disjunctions, except within queries. Consequently, simple properties of the CIDOC CRM that imply a temporal order, such as P134 continued, cannot be declared as subproperties of the temporal relationship they do imply, which would be, in this case: “before, meets, overlaps, starts, started-by, contains, finishes, finished-by, equals, during or overlapped by” (see P174 starts before the end of). Secondly, nature does not allow us to observe equality of points in time. There are three possible interpretations to this fact. Common to all three interpretations is that they can be described in terms of fuzzy boundaries. The model proposed here is consistent with all three of these interpretations.

Consider, for instance, a birth. Extending over a limited and non-negligible duration in the scale of hours it begins and ends gradually (1), but can be given alternative scientific definitions of start and end points (2), and neither of these can be determined with a precision much smaller than on a scale of minutes (3). The fuzzy boundaries do not describe the relation of incomplete or imprecise knowledge to reality. Assuming a lowest granularity in time is an approach which does not help, because the relevant extent of fuzziness varies at a huge scale even in cultural reasoning, depending on the type of phenomena considered. The only exact match is between arbitrarily declared time intervals, such as the end of a year being equal to the beginning of the next year, or that “Early Minoan” ends exactly when “Middle Minoan” starts, whenever that might have been. Consequently, we introduce here a new set of “temporal relation primitives” with the following characteristics:

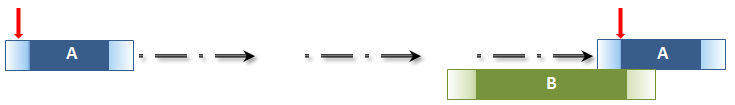

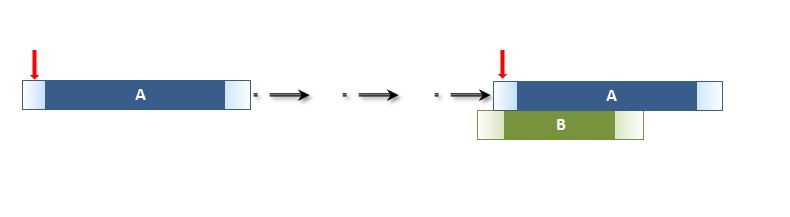

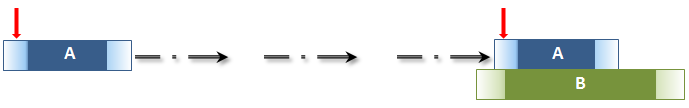

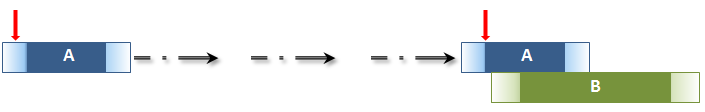

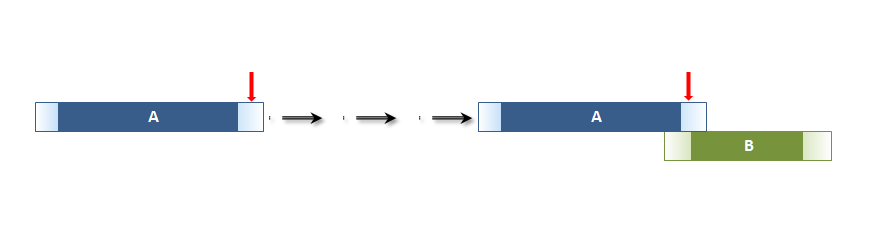

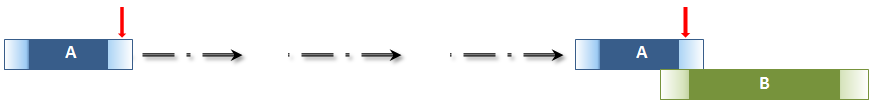

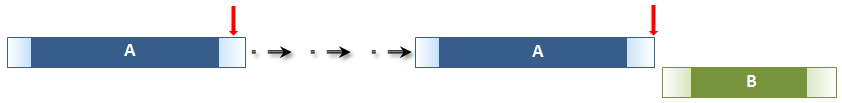

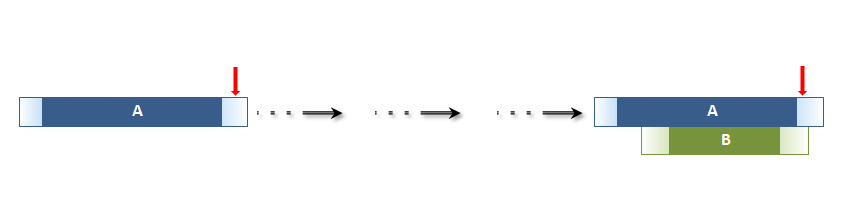

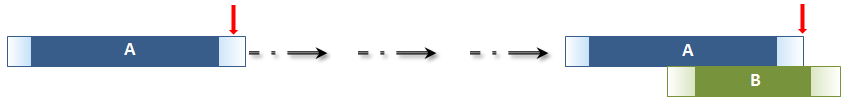

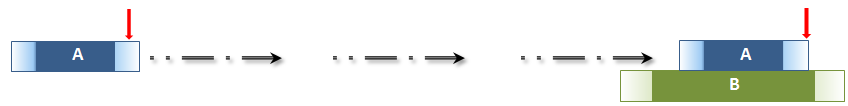

We use the following notation: Comparing two instances of E2 Temporal Entity, we denote one with capital letter A, its (fuzzy) starting time with Astart and its (fuzzy) ending time with Aend, such that A = [Astart,Aend]; we denote the other with capital letter B, its (fuzzy) starting time with Bstart and its (fuzzy) ending time with Bend, such that B = [Bstart,Bend]. We identify a temporal relation with a predicate name (label) and define it by one or more (in)equality expressions between its end points, such as: A starts before the end of B if and only if (⇔) Astart < Bend We visualize a temporal relation symbolizing the temporal extents of two instances A and B of E2 Temporal Entity as horizontal bars, considered to be on a horizontal time-line proceeding from left to right. The fuzzy boundary areas are symbolized by an increasing/decreasing colour gradient. The different choices of relative arrangement the relationship allows for are symbolized by two extreme allowed positions of instance A with respect to instance B connected by arrows. The reader may imagine it as the relative positions of a train A approaching a station B. If the relative length of A compared to B matters, two diagrams are provided.

Figure 7: Explanation of Interior and Boundary and an Example of Use from P174 starts before the end of (ends after the start of). Overview of Temporal Relation Primitives The final set of temporal relation primitives can be separated into two groups:

Improper inequalities with fuzzy boundaries are understood as extending into situations in which the fuzzy boundaries of the respective endpoints may overlap. In other words, they include situations in which it cannot be decided when one interval has ended and when the other started, but there is no knowledge of a definite gap between these endpoints. In a proper inequality with fuzzy boundaries, the fuzzy boundaries of the respective endpoints must not overlap, i.e., there is knowledge of a definite gap between these endpoints, for instance, a discontinuity between settlement phases based on the observation of archaeological layers. Table 2: Temporal Relation Primitives

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class & Property Hierarchies |

||

Although they do not provide comprehensive definitions, compact mono-hierarchical presentations of the class and property IsA hierarchies have been found to significantly aid comprehension and navigation of the CIDOC CRM. Since the CRM is poly-hierarchical, a mono-hierarchical presentation form is achieved by a top-down expansion of all inverse IsA relations regardless whether a concept has already be presented at another place in the same hierarchy. This form is provided below. The class hierarchy presented below has the following format:

The property hierarchy presented below has the following format:

|

||

| Class & Property Hierarchies >> CIDOC CRM Class Hierarchy |

||

| Automatically generated content | ||

| Class & Property Hierarchies >> CIDOC CRM Property Hierarchy |

||

| Automatically generated content | ||

| CIDOC CRM Class Declarations |

||

The classes of the CIDOC CRM are comprehensively declared in this section using the following format:

|

||

| E1 CRM Entity |

||

| Class Name: | ||

| CRM Entity |

CRM Entity

|

|

| SubClass Of: | ||

| - | - | |

| SuperClass Of: | ||

| E2 Temporal Entity E52 Time-Span E53 Place E54 Dimension E59 Primitive Value E77 Persistent Item E92 Spacetime Volume |

E2 Temporal Entity E52 Time-Span E53 Place E54 Dimension E59 Primitive Value E77 Persistent Item E92 Spacetime Volume

|

|

| Scope Note: | ||

This class comprises all things in the universe of discourse of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model. It is an abstract concept providing for three general properties:

All other classes within the CIDOC CRM are directly or indirectly specialisations of E1 CRM Entity. |

This class comprises all things in the universe of discourse of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model. It is an abstract concept providing for three general properties:

All other classes within the CIDOC CRM are directly or indirectly specialisations of E1 CRM Entity. |

|

| Examples: | ||

|

|

|

| In First Order Logic: | ||

|

||

| Properties: | ||

| P1 is identified by (identifies): E41 Appellation P2 has type (is type of): E55 Type P3 has note: E62 String P48 has preferred identifier (is preferred identifier of): E42 Identifier P137 exemplifies (is exemplified by): E55 Type |

||

| E2 Temporal Entity |

||

| Class Name: | ||

| Temporal Entity |

Temporal Entity

|

|

| SubClass Of: | ||

| E1 CRM Entity | E1 CRM Entity

|

|

| SuperClass Of: | ||

| E3 Condition State E4 Period |

E3 Condition State E4 Period

|

|

| Scope Note: | ||